June 25-26, 2015 – Klondike Area, Yukon Territory – Prospecting with a pan or a sluice started the rush, but this soon gave way to consolidation of claims and industrialization. The king of the industrial mining machines was the gold dredge. The dredge of wood and iron is a testament to engineering of the early 1900s. It is a huge boat floating in a man-made pond. Scooping up gravel in front, extracting gold on board, and dumping the gravel behind it. Inching its way up a stream at half a mile per working season. Bringing water and electricity to the dredge required other engineering marvels as well. The dredging process reshapes the landscape in ways that we would find entirely inappropriate today, but in a world where this was months away from civilization in the middle of an unimaginably huge wilderness that was less of a concern. A drive out into the Klondike valley, and a visit to Dredge Number Four is a glimpse into history and worth the drive, even if you don’t take a tour of the dredge itself.

The story begins with the land and erosion. As rivers flow they erode the underlying rock and carry it away downstream. The tumbling action caused by the flowing water continues to break the rock down into smaller pieces, eventually to sand. As this happens bits of trapped gold or gemstone locked up in the rock is released. Gold and other precious minerals and gemstones are much heavier than other rock, so the bits tend to collect at the bottom of these river beds. Over the millennia the land has been lifted and shifted so that flowing water on the surface has been rerouted. The Klondike seems to have been host to many such changes and so prospecting may turn up gold in gravel now high on a hill or under a flowing river. The dredge was generally for areas that are in the bottom lands, especially on current streams or along rivers, by another name: “Alluvial Deposits”.

The story begins with the land and erosion. As rivers flow they erode the underlying rock and carry it away downstream. The tumbling action caused by the flowing water continues to break the rock down into smaller pieces, eventually to sand. As this happens bits of trapped gold or gemstone locked up in the rock is released. Gold and other precious minerals and gemstones are much heavier than other rock, so the bits tend to collect at the bottom of these river beds. Over the millennia the land has been lifted and shifted so that flowing water on the surface has been rerouted. The Klondike seems to have been host to many such changes and so prospecting may turn up gold in gravel now high on a hill or under a flowing river. The dredge was generally for areas that are in the bottom lands, especially on current streams or along rivers, by another name: “Alluvial Deposits”.

Placer mining is looking for gold in alluvial deposits, this is loose rock, usually gravel. But “loose” is a term that is problematic in the cold north. Permafrost is typically a few inches to a few feet or so below the surface. That is to say that the soil has stayed frozen at that depth year over year. Across the north you can get a feel for the depth of the “live” soil above the permafrost by looking at the size of the trees. Further north, huge forests of black spruce blanket the hills where permafrost is only inches below the surface. These trees grow so slowly that the “trunk” of a one hundred year old tree may only be as big as a quarter in cross section. The wood so hard that driving a nail into it is nearly impossible. Taller trees may find a home in a foot or more of live soil, and this is more the norm here.

The prospectors identify deposits worth mining by drilling holes deep down to the bottom of the gravel. This bottom is usually bedrock, and that is where the heavy gold should have come to rest. The process of drilling through permafrost really relies on thawing the ground ahead of the drill. This is typically done with water. The water carries a little heat, which is transferred to the frozen ground and thaws it slowly. Originally this was done with steam, but they found that cold water was nearly as effective and much less trouble. In fact the trick for horizontal mining (not so much for drilling) turned out to be using water at pressure, or “Hydraulic Mining” to both thaw and move the gravel as it thawed so the gravel below was exposed.

The prospectors identify deposits worth mining by drilling holes deep down to the bottom of the gravel. This bottom is usually bedrock, and that is where the heavy gold should have come to rest. The process of drilling through permafrost really relies on thawing the ground ahead of the drill. This is typically done with water. The water carries a little heat, which is transferred to the frozen ground and thaws it slowly. Originally this was done with steam, but they found that cold water was nearly as effective and much less trouble. In fact the trick for horizontal mining (not so much for drilling) turned out to be using water at pressure, or “Hydraulic Mining” to both thaw and move the gravel as it thawed so the gravel below was exposed.

Before a dredge can start working, the land has to be prepared. To do this the overlaying trees, rocks, soil, buildings and the like needed to be removed. Now to work the gravel, the ground has to be thawed, all the way to the bedrock. So when frozen gravel was uncovered, hollow steel “thawing” points were driven into the ground and water pumped in. It typically took five years to prepare a site for a dredge to start working.

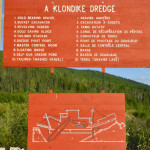

A dredge is really a huge automated gold pan. But the scale is hard to fathom without seeing it. A huge line of scoops brings gravel on board where water is sprayed over it to wash the gravel through meshes. That gravel is then processed by washing and mechanical action to trap finally only the heaviest bits. The gravel and sand that is left over is carried out a long conveyor and piled behind the dredge. The dredge itself floats on water in a man-made pond over the gravel bed. Pivoting on a piling driven into the bottom of the pond the dredge turned a crescent and then was drawn forward and swept back. The constant scooping at one end and piling at the other makes the pond move along. Leaving crescent shaped piles of gravel like a solid wake. The dredge moved along on the order of half a mile per eight month working season.

A dredge is really a huge automated gold pan. But the scale is hard to fathom without seeing it. A huge line of scoops brings gravel on board where water is sprayed over it to wash the gravel through meshes. That gravel is then processed by washing and mechanical action to trap finally only the heaviest bits. The gravel and sand that is left over is carried out a long conveyor and piled behind the dredge. The dredge itself floats on water in a man-made pond over the gravel bed. Pivoting on a piling driven into the bottom of the pond the dredge turned a crescent and then was drawn forward and swept back. The constant scooping at one end and piling at the other makes the pond move along. Leaving crescent shaped piles of gravel like a solid wake. The dredge moved along on the order of half a mile per eight month working season.

The bucket line laid out along the path lies stationary with the enormous weight of iron, but its regularity reminds one that it was designed to be ever in motion. It is much like the chain of a chainsaw, but on a giant’s scale. Each bucket is a link, made of iron, typically with a hardened edge or tooth. Huge pins link the front of one bucket to the back of the next so they can flex as they roll over the front and back of the boom. When these lines came off their tracks the work to put them back required more than just a pry bar. The bucket line of dredge number four scooped up about a standard dump truck load of gravel every minute, processing and dumping the same amount as it moved along.

The bucket line laid out along the path lies stationary with the enormous weight of iron, but its regularity reminds one that it was designed to be ever in motion. It is much like the chain of a chainsaw, but on a giant’s scale. Each bucket is a link, made of iron, typically with a hardened edge or tooth. Huge pins link the front of one bucket to the back of the next so they can flex as they roll over the front and back of the boom. When these lines came off their tracks the work to put them back required more than just a pry bar. The bucket line of dredge number four scooped up about a standard dump truck load of gravel every minute, processing and dumping the same amount as it moved along.

It only took a few people to crew the dredge itself. Their job was to keep the dredge working 24 hours a day, seven days a week, scooping and washing. They would pause the dredge every three or four days to collect the gold from the sluice and send that down to the camp where it was made into bars. Of course when things broke that meant frantic work to get it back to working. So the mining companies built huge shops to produce and repair the dredges. Workers were also needed to clear land and prep sites.

Water was key to this kind of operation, and several projects were undertaken to bring water from surrounding areas. Notably the Yukon Ditch which brought water from the Tombstone mountains over 70 miles to generate electricity and for hydraulic mining.

The dredges would leave behind a landscape that looks like it was created by some otherworldly process. Crescent shaped piles of gravel all the same height march up the valley. As you drive into Dawson City you will drive through miles of this kind of landscape, and to varying degrees be able to see it. The higher your vantage point from car, truck or bus the better you will see it. But you should stop and get a higher vantage point to see it clearly. Photos from the car or side of the road don’t do it justice, but your eye tells you this isn’t natural.